Richard Hyfler, 27 February 2008

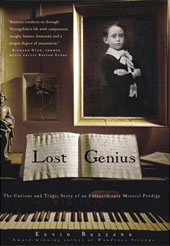

An interview with Kevin Bazzana, author of Lost Genius ($28, Carroll & Graf, 2007).

Born in 1903, Hungarian pianist Ervin Nyiregyházi (pronounced air-veen nyeer-edge-hah-zee) played Buckingham Palace at age 8, was the subject of a book by the time he turned 13 and soon enjoyed critical success on two continents.

As an adult, he was an alcoholic, addicted to paid sex and afraid to perform in public on the piano. His career foundered, despite champions as diverse as Bela Lugosi and Arnold Schoenberg, and he spent decades living in poverty, mostly in a succession of cheap hotel rooms in California, even after his rediscovery and a brief period of international celebrity in the 1970s.

Since his death in 1987, fans have created numerous Web sites devoted to his career and the few recordings that are available. Concert recordings from the ’70s have recently been issued on a two-disc set by Music & Arts, CD 1202. But, his biographer says, there are good reasons for music lovers–and particularly musicians–to look beyond Nyiregyházi’s idiosyncrasies.

Forbes.com: Considering Nyiregyházi’s frequent lack of a fixed address or income, it seems a small miracle that so much documentary material on his life has survived.

Bazzana: I was forced to become a detective in order to write Nyiregyházi’s story. He left little footprints all over the world–quite a lot of information, but widely scattered. I had to track it all down and reassemble it in order to tell his story; it took 10 years. If I were writing the story 50 years ago, I would have had to travel all over the world; however, I was able to do almost all of my detective work by long-distance, with only a little travel. Through mail, e-mail, telephone, microfilm, etc., I was able to conduct interviews and acquire information from Hungary, Germany, Scandinavia, England, Japan, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago and many other places.

One trove of material proved particularly valuable: the personal effects of Nyiregyházi’s 10th wife, Doris–which included the personal effects of Nyiregyházi himself. After she died in 2001, I was able to study all of her effects, including the results of hundreds of hours of interviews she conducted with him about every aspect of his life and work. She originally wanted to write his biography herself.

I’m confident that I ferreted out most of what is there to be found. Still, he was such an eccentric person, and his life was so bizarre, that I sometimes dread finding, too late, some startling tidbit that wasn’t available to me when I was writing the book. With a character like this, who knows what might be hiding in that one dark corner I wasn’t able to look into while writing the book!

Are there historical figures in music, or in the other arts, who, by virtue of their combination of talent and lack of success, might be compared to Nyiregyházi?

In the conclusion of the book, I wrote: “The spectacularly gifted but psychologically cursed artist who seems reluctant to practice his art is a type uncommon but not unknown.”

When I wrote this, I was thinking of artists like the writer J. D. Salinger, the conductor Carlos Kleiber, the pianist Glenn Gould, the actors Louise Brooks and Marlon Brando, the chess master Bobby Fischer. These are artists of incredible talent and individuality, yet the price of their particular gift was the kind of psychology that seemed not to permit them to enjoy an ordinary career and the high productivity that their fans would have liked.

Salinger simply couldn’t stand being famous, and so refused to be a public figure any longer, even to the point of refusing to publish anything. Kleiber is widely considered the greatest conductor of our time, yet his perfectionism made it scarcely possible for him to conduct; his output was tiny, highly selective–yet of unrivaled quality. Gould had so many personal and musical hang-ups about live performance that he quit the concert scene entirely and retreated to the recording studio. Brooks and Brando simply couldn’t stomach what was required to have a Hollywood career; you are left with the irony of someone of Brando’s talent and individuality being so convinced of the triviality of what he does that he’s scarcely willing to do it anymore! And Fischer, well …

Some of these figures had huge success; some had limited success; some had success and then failure. But what they all had in common was a particular kind of gift that was incompatible with the normal professional exercise of that gift.

It’s a tragedy, really, because those artists with that particular kind of career-sabotaging psychology are often the greatest and most individual of all. We can only sigh heavily, and accept them as they are and be grateful for what little of them we have.

Your previous book, Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould, is also an account of an eccentric pianist. Gould’s style and approach to the piano literature still exert an influence on contemporary pianists. Why should musicians listen to the few existing Nyiregyházi recordings?

Of the two, one could argue that Nyiregyházi was actually the more historically important figure. Gould was a spectacularly gifted and dynamic example of a kind of playing that was increasingly the prevailing trend in his day: All the pianists of Gould’s generation were playing Bach in a more streamlined, transparent, analytical, historically informed style than had been the case previously; Gould was particularly influential but reflected larger trends in performance.

When Nyiregyházi reappeared on the scene in the 1970s, he was a like a living fossil–an authentic representative, still living and playing, of a long-lost style of musical performance. Musicians and critics spoke of Nyiregyházi’s performing style as “old-fashioned,” even when he was a child. The particular kind of hyper-Romanticism he advocated was going out of style with increasing rapidity after the first World War, around the time Nyiregyházi was emerging as a professional.

He represented an approach that was associated with the heyday of Romanticism in the mid-19th century, the era of Liszt, Hans von Bülow, Anton Rubinstein, etc.–pianists who never lived into the recording era. Only a few older pianists who lived to make recordings reflected the kind of arch-Romanticism Nyiregyházi did–Busoni, for instance, and Paderewski.

Nyiregyházi stood apart from the trend toward a less indulgent, more “modern” style of playing, a trend that grew in the years between the wars. It’s no wonder his style made him less and less palatable to critics and fellow musicians as time passed. And when he reemerged he seemed like a genuine specimen of 19th-century Romanticism preserved in amber. Performers of 19th-century repertoire could actually learn a lot from him about what “Romanticism” really means. Nyiregyházi, needless to say, didn’t think much of the “play it the way it’s written” approach of modern performers.

To many modern listeners, Nyiregyházi’s style seems excessive, sentimental, grotesque, self-indulgent, disrespectful, etc.–and yet, when you study what 19th-century musicians had to say about performance, you realize that Nyiregyházi was a more genuine Romantic than those modern performers who play Romantic music in a more “respectful” manner.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.