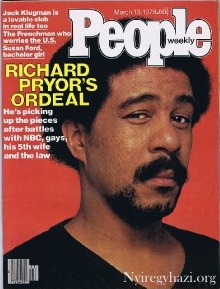

March 13, 1978, Vol. 9, No. 10

For Pianist Nyiregyhazi, Fame, Unjustly, Is Nine Wives and Ten Photographed Fingers

When I play, it’s as though I am Franz Liszt himself,” says Californian Ervin Nyiregyházi. Even critics accept the braggadocio. A century back, composer Liszt was himself a child-prodigy pianist, flamboyant maestro and herculean womanizer. His reincarnation, also Hungarian-born, was a student of two of Liszt’s disciples, an ex-prodigy who turned prodigal wastrel in the 1920s when he married

Latter-day fanciers of his 19th-century Sturm und Drang were first re-reminded of Nyiregyházi’s genius when he burned through six of Liszt’s “appassionatas” in a Desmar LP issued 18 months ago by International Piano Archives (IPA). Yet as recently as last December, its performer was living in a seedy Los Angeles area with no hope of a second fling with fame. Then the record was played for the Ford Foundation, which provided $38,000 for the IPA. That grant finally got the old gent into a decent sound studio with a concert grand worthy of his skills and all the hi-fi gadgetry needed to hold his astonishing sonorities (which seem at least a few dozen decibels beyond the power of his frail forearms). On his way to the piano—he hasn’t owned one for 40 years, has an astonishing photographic memory for scores and never did practice much—Nyiregyházi must lean on his cane. But without it he can stand at a bar and down highballs with heroic endurance.

Yet he was stone sober in San Francisco a few weeks ago cutting the astounding tapes subsidized by the foundation. When they were played for distributors in New York, CBS Records rushed in with an offer to mark the old man’s return with a three-LP album—an unprecedented show of confidence in a forgotten artist who has no intention of ever turning up on the recital circuit to promote sales. His records—despite overwrought patches, added and even wrong notes—will drive even some Horowitz and Rubinstein idolators to rank Ervin Nyiregyházi in their class. No expert can deny that he is the world’s greatest at the gaudy craft of freestyle Liszting.

When he made his U.S. debut at Carnegie Hall in 1920, the Budapest native was called “a 17-year-old Paderewski.” Five years later he was tagged in the trade as too temperamental to deal with, and when his career died from litigation with managers and a dearth of recital dates, he turned indigent. “I had to sleep on the New York subway,” he says. In 1926 he married for the first time, a woman 11 years older. Shortly thereafter Ervin was arrested on Madison Avenue wearing purple pajamas. His wife had hidden his pants, suspecting he wanted to visit a girl, which, of course, he did. “I had to run away,” says Nyiregyházi, who went first to the pad of novelist friend Theodore Dreiser and later to California. He has spent the 50 years since lining up and leaving—or being left by—wives. Six marriages ended in divorce; three wives died.

Over the years the pianist moved a number of times from California (where he was naturalized in 1940) to Europe and back while composing 1,300 piano and orchestral scores. To stay at least marginally solvent, he played in WPA orchestras around L.A. (for $94.08 a month) and did Hollywood hack work. His hands were filmed as Chopin’s in the movie of his life and as Liszt’s in Song of Love, the story of Clara and Robert Schumann. And all of Nyiregyházi—with distorted face and fingers punching out a Liszt Mephisto Waltz—starred in the B horror flick Soul of a Monster.

His situation worsened after that, and he moved into the slums, where he was robbed and mugged often enough to learn to stay inside after 6 p.m. In 1972 he performed publicly for the first time in 17 years to pay the doctors’ bills for his most beloved and then dying wife No. 9. The next year he played a few more recitals, including one at a San Francisco church, where he was discovered by an IPA representative, who taped the performance on a portable cassette.

Now, with some riches possibly around the corner, Nyiregyházi thinks there might even be another wife. “It’s a real problem,” he allows. “If I were 10 years younger it wouldn’t be such a hopeless task.” But, unlike exemplar Liszt, he has no intention of trying to live without women by moving into the Vatican. Exults Nyiregyházi: “I never give up hope.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.