Los Angeles Times:

A spiritual connection: Ervin Nyiregyházi, Louis ‘Moondog’ Hardin and, yes, Bobby Fischer

CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK

By Mark Swed

January 27, 2008

DURING the 1970s, I often spent time in the music room of the L.A. Central Library. One other regular was an elegant, if seedy, older gentleman, always dressed in the same threadbare suit and tie and loath to remove his jacket, even in the summer. He was, I later learned, a famed Hungarian pianist who had fallen on hard times and lived in flophouses downtown.

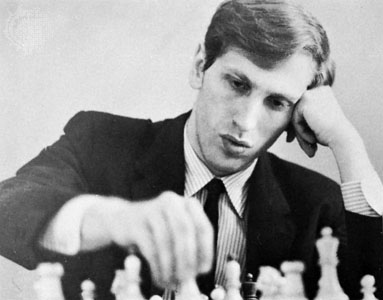

I’m pretty sure I also saw Bobby Fischer once or twice on the library lawn, where derelicts then gathered, studying a portable chess board. He too, word had it, lived for a period in flophouses downtown.

Did Ervin Nyiregyházi ever notice Fischer? It’s possible. The pianist, who, in his youth in Budapest was called the second Liszt, would have recognized the grandmaster; Nyiregyházi (pronounced NEAR-edge-hah-zee) was passionate about chess and a fan of Fischer.

The two, it dawned on me as I read obituaries of Fischer this month, had much in common. Fischer is widely held to have been the greatest genius the world of chess has ever known. Arnold Schoenberg said of Nyiregyházi, who’s the subject of a new biography, that he was “the person most replete with genius I have ever heard.” Both geniuses became impossible social misfits who self-destructed after spectacular careers.

As it happens, a biography has recently been published of yet another remarkable nut case: Moondog, a composer and performer who became a noted street person in New York in the 1950s and ’60s. I had already been thinking about the surprising similarities between Nyiregyházi and Moondog, who died, respectively, in 1987 and 1999, when the news came of Fischer’s death in Iceland. The initial coincidence that the first biographies of these two inexplicable musical eccentrics would come out about the same time struck me as more than a little curious. But now the links to Fischer seem uncanny — and possibly revelatory.

As it happens, a biography has recently been published of yet another remarkable nut case: Moondog, a composer and performer who became a noted street person in New York in the 1950s and ’60s. I had already been thinking about the surprising similarities between Nyiregyházi and Moondog, who died, respectively, in 1987 and 1999, when the news came of Fischer’s death in Iceland. The initial coincidence that the first biographies of these two inexplicable musical eccentrics would come out about the same time struck me as more than a little curious. But now the links to Fischer seem uncanny — and possibly revelatory.

The two composers’ careers took parallel paths, but they came from radically different worlds. Louis Hardin, who was born in 1916 and who called himself Moondog, was the son of a Midwestern preacher who regularly ran afoul of the church. At 16, the shy, despondent Louis, never recognized as remarkable, was blinded when he found a detonator cap that had been left behind by a construction crew and it exploded. Blindness triggered his mania for music and his fierce independence.

Born in 1903 in Budapest, Nyiregyházi, on the other hand, was by age 6 recognized for having the most perfect pitch ever measured, along with a superhuman memory and a prodigious piano technique. As a long-haired boy in short pants, he was paraded about by ambitious parents like the young Mozart and performed for royalty. He was gifted at chess as well and could beat some of the best in Budapest blindfolded. In 1910, a Hungarian psychologist began a four-year study of the boy, who became the subject of the first book on the nature of child prodigies.

Hardin attended the Iowa School for the Blind and studied music at the Southern College of Music in Arkansas. Nyiregyházi’s first piano teacher had been a pupil of Liszt. The student impressed Richard Strauss, Puccini, Goldmark, Lehár and Reger. He played Buckingham Palace and entertained Bismarck and Einstein.

At 15, Nyiregyházi was forced by his mother to still perform in short pants and keep his hair long, preposterously milking his value as a prodigy, until he finally rebelled. Hardin, in exactly the reverse fashion, would eventually grow unfashionably long hair and design his own preposterous clothes. Nyiregyházi was pampered as a child and could barely button his shirt. Moondog was so fiercely independent that he insisted, though blind, on sewing his own clothes. Nyiregyházi was a natty tidiness freak; Moondog was a hopeless slob whose trademark became the Viking helmet that he took off, most of his life, for no one.

Yet the personalities of Hardin and Nyiregyházi are described in nearly identical terms in Robert Scotto’s “Moondog: The Viking of Sixth Avenue” and Kevin Bazzana’s “Lost Genius: The Curious and Tragic Story of an Extraordinary Musical Prodigy.” Bazzana — whose book is quite a page turner (Scotto’s prose is more labored) — writes of Nyiregyházi that he was introverted, shy, neurotic, deeply melancholic, paranoid, bitter, angry, resentful, defiant, quick to hurt. His sense of entitlement was extraordinary. One critic called him “a mad dog.” The same or similar terms turn up in the Moondog biography.

Hardin and Nyiregyházi both rebelled against censorious mothers (the former’s cold and distant, the latter’s a stage mother from hell), broke off from their families and fled to New York the first chance they got. And before long, both wound up on the street.

When he arrived in New York in the early ’20s, Nyiregyházi wowed audiences, impressed critics, amazed colleagues. But his career went nowhere. He was high-minded, easily insulted and easily victimized by unscrupulous managers. He was easily distracted by women as well. His life became a series of highs and lows — one minute part of glittering society, the next down and out. Sometimes he was in demand in the great concert halls; at other times he was forced to play parties to pay for his drinks.

The young Hungarian discovered sex late but became, and remained, obsessed with it. He married for money, married for love, married for sex, married for convenience. In the end, he’d had 10 wives, along with hundreds of affairs. He claimed it was his tremendous libido that made him the tremendous pianist he undoubtedly was.

Moondog moved in and out of celebrity too. During his first years in New York in the early ’40s, he sort of fit into the bohemian world. He was a proud bum who wrote his own quirky music, invented his own quirky instruments, made his own quirky clothes and panhandled. In 1947, he began calling himself Moondog.

Early on, he caught the attention of Artur Rodzinski, music director of the New York Philharmonic and a conductor with a spiritualist bent. Rodzinski thought Moondog had the face of Christ and invited him to rehearsals. Players in the orchestra took Moondog under their collective wing, and he became a good luck charm for the ensemble. Rodzinski’s wife (with whom Nyiregyházi likely had an affair) was alternately attracted to and repulsed by Moondog, with his long hair, long beard and thin, delicate features. But Moondog had no intention of fitting into polite society, sold the fine clothes Rodzinski gave him and managed to offend conductor, wife and players in short order.

It took a while for Moondog to develop his style, but by the late ’50s he had become a New York icon, with his clothes sewn of square patches of fabric and leather and his Viking helmet. He had his spot in Midtown on 6th Avenue, where he played his music, recited his poetry and begged for money. Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Dean Martin, Charlie Parker, Cassius Clay, Leonard Bernstein and Marlon Brando dropped by. Joan Baez named her dog Moondog. In pre-Beatles 1959, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison formed a band, Johnny and the Moondogs. Philip Glass took Moondog in for a year.

But sooner or later, Moondog bit every hand that fed him. He was intolerant. He worshiped Nordic culture. He was anti-Semitic and racist. He married a couple of times but had a reputation for being gross and inappropriate around women. A recording of his music released on Columbia Records in 1969 made him a brief sensation, but it didn’t last.

Nyiregyházi wound up in Los Angeles for the later part of his life, and he was often around celebrities. Fellow Hungarian Bela Lugosi was a kindred spirit. Gloria Swanson took an interest in him. He got a bit of work in the pictures (those are his hands in “A Song to Remember” and “The Beast With Five Fingers”). Schoenberg went to bat for him. But he had a reputation for being a womanizer, a drunk, unreliable, temperamental.

Like Moondog, who eventually emigrated to Germany, where he lived the latter part of his life somewhat better cared for than in New York, Nyiregyházi had a racist streak and a peculiar anti-Semitic one as well. Although he was Jewish, he once called Hitler a great man for killing the pianist’s mother, who died in the Holocaust.

No other pianist like him

A few years after attempting to create a Moondog sensation, Columbia discovered Nyiregyházi and made a Liszt recording that turned him too into a brief sensation. It proved too little, too late. He was too old and too far gone to begin a career all over again. “I’m addicted to Liszt, oral sex and alcohol — not necessarily in that order,” he said at the time.

The Music and Arts label has just released two CDs’ worth of late, live Nyiregyházi performances. Taken from recitals in out-of-the-way venues in San Francisco in the early ’70s and in Japan in the early ’80s, these are weird documents of a riveting, if somewhat demented, pianist who tends to begin a Chopin or Liszt piece in a quiet way and then shocks you with a massive climax. He can be insanely slow or insanely fast or just plain insane. He misses notes but still has an astounding technique. There was no modern pianist like him.

Nyiregyházi wrote, it is believed, more than 1,000 pieces. So did Moondog. And both were bizarre composers. Although none of Nyiregyházi’s music is readily available to hear, Bazzana describes high-minded compositions exalting Caesar, Kant, Dostoevski, Oscar Wilde. He also lists Nyiregyházi’s “Phantasmagoria of Pat Nixon,” “The Beheading of Pat Nixon” and “It’s Nice to Be Soused,” along with an explicit musical description of erotic massage.

Moondog’s music, only a small fraction of which has been recorded, is equally strange, typically starting out simply and gradually building up contrapuntal structures of mind-blowing climactic complexity. Like Nyiregyházi, he was attracted to high-minded classics (particularly Viking lore), moody dirges (“All Is Loneliness”), the erotic (“Ode to Venus”) and the quotidian (“Coffee Beans”). His music has an element of swing, a hint of Minimalism and a lot of Bach. It needs to be better known.

But what to make of these guys? Bazzana and Scotto both take a psychological approach. The mothers loom large in these biographies. But that explains too little, especially about the music. Did these musicians have a neurological screw loose?

Oliver Sacks, in his new book, “Musicophilia,” describes a host of ways that music, for good and ill, can affect the brain. Daniel J. Levitin, in “This Is Your Brain on Music,” looks into musical obsessions and the scientific and emotional components of what goes into making a musician. But the subject is too vast to offer much help when we are confronted with a Moondog or Nyiregyházi.

Fischer’s example, which is more extreme, helps the most. He had many of the same traits as the two musicians, such as the anti-Semitism (he was even more virulent than Moondog and, like, Nyiregyházi, was Jewish). And like music, chess is an activity that requires the mastery of rules of a very strict order. Fischer was so much the master of the rules of chess, as these musicians were of the rules of their art, that he seemed to have no capacity to cope with those of society.

Fischer’s example, which is more extreme, helps the most. He had many of the same traits as the two musicians, such as the anti-Semitism (he was even more virulent than Moondog and, like, Nyiregyházi, was Jewish). And like music, chess is an activity that requires the mastery of rules of a very strict order. Fischer was so much the master of the rules of chess, as these musicians were of the rules of their art, that he seemed to have no capacity to cope with those of society.

But what I think the cases of all three geniuses ultimately come down to is a hopeless rebellion against the modern world. They simply were not men of their time. Nyiregyházi was the last great 19th century pianist, and his music, no matter how up-to-date its subject matter, was of the earlier century as well. Moondog was entirely unsuited to contemporary life, and he moved further and further away in time, back to Bach and Nordic myth.

For Fischer, the threat was the computer, which had the capacity to destroy the game that was his life. If his became the most extreme case of the three — a fugitive from justice who preached the destruction of America — it was only because he was the youngest and so the threat of the modern age was, for him, the greatest.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.